Free Education Guide!

Teachers and educators, download our free PDF education guide for this show, which will help you incorporate Chatterbox into your classroom!

Written by Marques Brown, Education Director.

Cast & Crew

Narrator: Jane Kilgore

John: Robert Arnold

Jennie: Katherine Whitfield

Musician: Jeremy Howard

Sound Effects: Katherine Whitfield

Dramaturge: Rebecca Bates

Producer: Andrew Sullivan

Adaptation: Robert Arnold

Director: Robert Arnold

Announcer: Tom Badgett

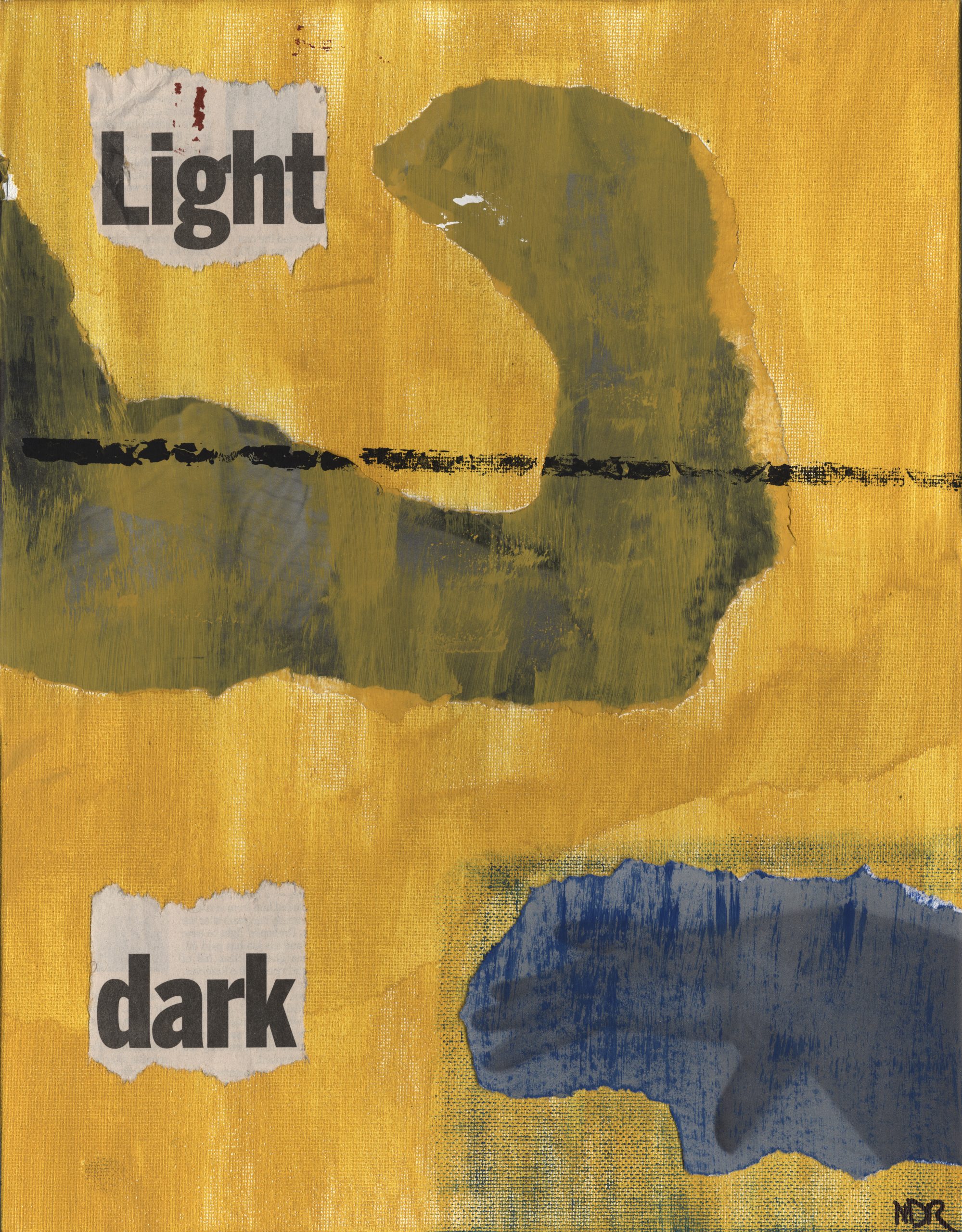

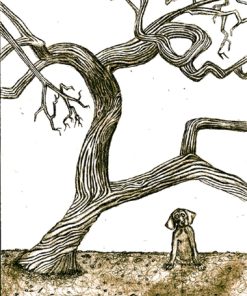

Artist: Matt Reed

Notes

Spoiler alert! Don’t read these notes if you don’t want the ending of the story revealed.

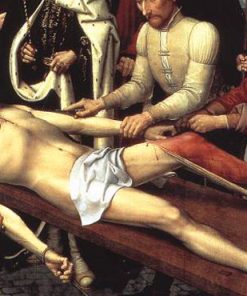

In 1887, Charlotte Perkins Gilman found herself suffering from “a severe and continuous nervous breakdown tending toward melancholia — and beyond.” Upon seeking professional help, she was advised against more than two hours of intellectual stimulation a day, and was ordered to cease writing, drawing, and painting for the remainder of her life. Three months passed in which Gilman strictly observed these commands. But by ignoring her life’s work, even for this seemingly brief period of time, she thrust herself so far into depression that complete mental destruction appeared inevitable. Only by finally renouncing the physician’s directions did Gilman escape such a fate.

In the aftermath of her brush with insanity, Gilman wrote “The Yellow Wallpaper” as a warning against submitting to subjugation of the mind. As the narrator experiences the same rest cure as Gilman, her mental health declines and she begins to imagine women trapped within the pattern of her bedroom’s wallpaper. Her husband’s condescending tone coupled with the narrator’s own acquiescence to his close-minded views on her illness eventually lead to her psychological ruin.

The narrator’s acceptance of the repression inflicted by her husband is evident early in the story. After commenting on her suspicions about the house, the narrator says of her husband, “John laughs at me, of course, but one expects that in a marriage.” This comment, though simply meant as an aside, establishes the denigrating quality of the husband-wife relationship. Yet the particularly disturbing aspect of this interaction is the way in which the narrator passively accepts John’s patronizing attitude. This is a recurring theme throughout the story. Though John refuses to believe that the narrator suffers from anything more than a nervous depression, the narrator’s constant response is “But what is one to do?” The repetition of this phrase indicates the way in which the narrator assigns herself a sense of helplessness. And this seems to be the narrator’s downfall. She begins to adopt John’s language when she says, “I take great pains to control myself — around [John] at least, and that makes me very tired.” By using his vocabulary to describe her own condition, she becomes restricted by John’s rigid and limited capacity of emotion and feeling.

Perhaps Gilman wanted this tyranny of mind to be viewed as a widespread challenge for women. As the narrator hallucinates about women in the wallpaper, she wonders whether “there are a great many women behind, and sometimes only one…” The numerous women create a unifying effect of one voice in an effort to reflect the pervasiveness of this repression. Ultimately, Gilman believed her work was “not intended to drive people crazy, but to save people from being driven crazy.”

—Rebecca Bates

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.