Cast & Crew

Aubert: Justin Willingham

Gerande: Shannon King

Scholastique: Jo Lynne Palmer

Pittonaccio: Bo List

Master Zacharius: Robert Arnold

Musician: Katherine Whitfield

Sound Effects: Karen Strachan

Sound Effects: Jonathan McCarter

Sound Effects: Jim Palmer

Producer: Andrew Sullivan

Adaptation: Robert Arnold

Director: Robert Arnold

Announcer: Tom Badgett

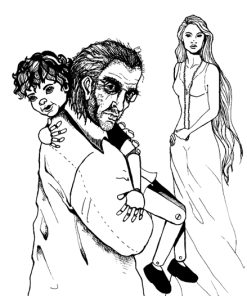

Artist: Erica McCarrens

Special Thanks to:

- Jim Thompson of EgglestonWorks

- Bill Short

- Eden Badgett

- Mike Hanrahan

- Kevin Barré of Kevin Barré Photography

Notes

Written in 1854 but not published until 1874, “Master Zacharius, or the Clockmaker Who Lost His Soul” might seem strangely technophobic for a Jules Verne story. After all, Verne (1828-1905) — who, along with H.G. Wells, is widely considered one of the fathers of science fiction — is famous for adventure stories that showcase marvelous technological innovations. In Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, From the Earth to the Moon, Around the World in Eighty Days, Journey to the Center of the Earth, and many more of his “Voyages Extraordinaires,” Verne imaginatively speculates on all the wonderful things that await humanity over the horizon of its progress.

How, then, to understand “Master Zacharius,” in which the strong-willed inventor and student of science foolishly rebels against humility and religious piety? At least one critic claims that Verne wrote the story to appease his devout father, who became enraged after learning that the younger Verne had abandoned a planned legal career. This may be, but more careful consideration of the story also suggests that Verne is using Zacharius to explore a theme that occupied him throughout his entire artistic life.

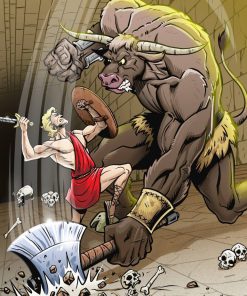

In Zacharius’s world, as in our own, science and technology are themselves morally neutral. Certainly there is nothing sinful in the Master’s invention of the escapement, a device that changes the continuous motion of gears into the periodic motion of a clock’s hands. The problem comes with Zacharius’s pride in his invention, and the grandiose claim that its creation has made him the equal of God. The story’s true evil, then, is named outright in the title of its second chapter: not science itself, but “The Pride of Science.”

Consider, too, the strange gentleman who shows up in Zacharius’s workshop. Though his bargain is undeniably Faustian, Signor Pittonaccio does not physically resemble Satan. Instead, he is described as — and he behaves just like — a clock. The story’s antagonist, then, is time itself, whom Zacharius petitions for eternal life, and who proves more difficult to regulate than the Master, in his boastfulness, would expect.

Verne’s longtime editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel had a famously strong influence on the author. Among other revisions, Hetzel encouraged Verne to imbue his narratives with happy endings and a general sense of optimism. Stories created outside of Hetzel’s influence reveal an abiding cynicism about the effect of technology on the human spirit. (Poignantly, Verne’s dystopian novel Paris in the 20th Century was deemed so gloomy by Hetzel that Verne locked the manuscript in a safe, where it was not discovered again until 1994, after the 20th century had nearly ended.) Written prior to Hetzel’s involvement and published after his grip on the artist had begun to loosen, “Master Zacharius” may actually reveal more of Verne’s true outlook than do the more upbeat narratives in his better-known works.

So — is Verne’s cynicism warranted? Can humankind pursue science and progress while avoiding a corrosive pride? Can we make moral choices in a world devoid of literal angels and demons? Of course we can. We just need the occasional reminder, which this story delivers beautifully, that true wisdom lies in admitting that, no matter how advanced we become, we still know practically nothing.

—Robert Arnold

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.